Potosí, Bolivia, uniquely allows the legal purchase of dynamite for public use, attracting tourists to experience mining traditions. The extensive mining history of Cerro Rico has made Potosí one of the poorest regions, despite its previous wealth. El Tío, a protective figure in mining culture, embodies the enduring spirit of locals, who continue to face harsh working conditions and health challenges in the mines.

Potosí, a Bolivian mining city, uniquely allows the legal purchase of dynamite by the public, making it a notable destination for adventurous tourists. During guided tours, visitors can experience the dramatic detonation of dynamite in the mountain’s mines, where they witness the rich history and labor practices that define the area. The price for dynamite is remarkably affordable, with a stick costing around 13 Bolivianos, equivalent to less than $2.

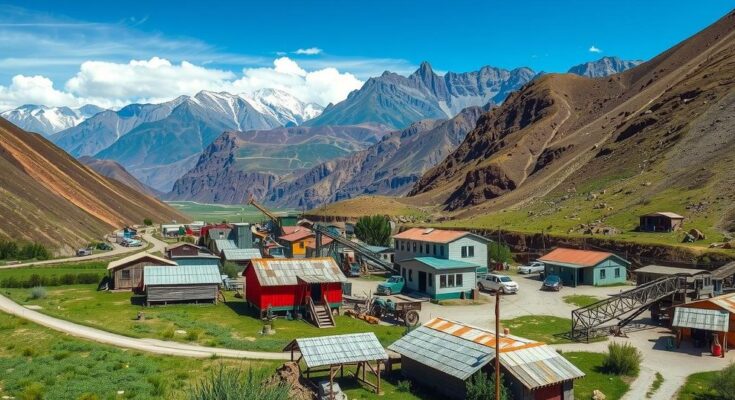

The extensive network of Potosí’s mines has historical roots dating back centuries, reflecting the Spanish colonial past and creating an evocative atmosphere reminiscent of adventure films. At an elevation of over 4,000 meters (13,000 feet), Potosí is one of the world’s highest cities. Today, however, it is regarded as one of the poorest regions in Bolivia, as stated by local tour guides, due in part to the depletion of resources over the years.

Cerro Rico, or “Rich Mountain,” was first discovered for its silver deposits in 1545 by indigenous prospector Diego Gualpa. This massive wealth attracted Spanish colonizers who exploited the mountain extensively, leading to a harsh labor system akin to enslavement for indigenous workers. Despite its initial prosperity, the mountain’s resources dwindled, resulting in difficult circumstances for both miners and the region.

The immense pressures of mining led the Cerro Rico to be nicknamed “The Mountain That Eats Men,” a phrase that resonates with miners today. The harsh mining conditions combined with the introduction of toxic materials caused significant health crises for communities involved in the trade. As mining practices shifted, Potosí produced mainly tin and zinc while the once plenary silver resources declined dramatically.

Local rituals remain vital to the mining culture in Potosí, where miners venerate El Tío, a horned devil-like effigy that symbolizes protection and prosperity. Miners offer gifts to El Tío, including coca leaves and spirits, hoping to receive good fortune and safety within the perilous mines. Some locals even conduct llama sacrifices at mine entrances to appease him, continuing a deeply rooted tradition.

Tragically, miners face a life expectancy of just 40 years due to accidents and respiratory diseases. Young children often join the labor force, sometimes as early as six years old, despite legal restrictions. Nevertheless, a sense of creativity blooms amidst the hardships, with miners expressing themselves through music, poetry, and annual carnivals that showcase their resilience and community spirit.

Potosí, a city steeped in rich mining history, presents a juxtaposition of adventure, tradition, and adversity. While the city allows for unique experiences such as purchasing dynamite and embarking on thrilling underground tours, it also embodies the struggles and harsh realities faced by its miners. As both a historical site and a living community, Potosí serves as a poignant reminder of the lasting impact of resource extraction and cultural persistence in the face of adversity.

Original Source: www.koamnewsnow.com